I opened my eyes to the sight of the ground rushing toward me. The pilot yanked back on the cyclic stick, inducing sickening Gs as the helicopter clawed toward the sky. We roared past the crash site, just feet from impact.

We’d done it! We’d re-created the Stevie Ray Vaughan helicopter crash. It made sense now. I could see it all so clearly. Stevie Ray Vaughan never saw it coming at all.

Stevie Ray Vaughan, perhaps the best rock/blues guitarist of my generation, was 35 when he died in a helicopter crash near Elkhorn, Wisconsin, shortly after midnight on August 27, 1990. I was only a few years younger than that when my boss, a seasoned aviation lawyer, dropped a new litigation file on my desk. Although still a “baby lawyer” at the blue-blood, Dallas law firm where I worked, I was older than most of the firm’s junior lawyers as a result of flying helicopters in the Army for five years before law school. The file landed on my desk because of my flying experience. I had over 1,000 hours of helicopter flight time under my belt, most of it in the same model helicopter that flew into a ski slope on that fateful night in 1990, killing Vaughan and everyone else on board.

My boss lingered at my door for a moment as I flipped through the file.

“This is the Stevie Ray Vaughan case,” I said, my curiosity piqued.

“Figure out what happened. There’s some big money at stake on this one. Ever heard of Bobby Brooks?”

I shook my head.

“Well, he’s the big money. He was Eric Clapton’s manager and one of the four passengers on the helicopter. He got a percentage of everything that Clapton made, and it doesn’t take much of a percentage of Clapton to make you a very wealthy individual.”

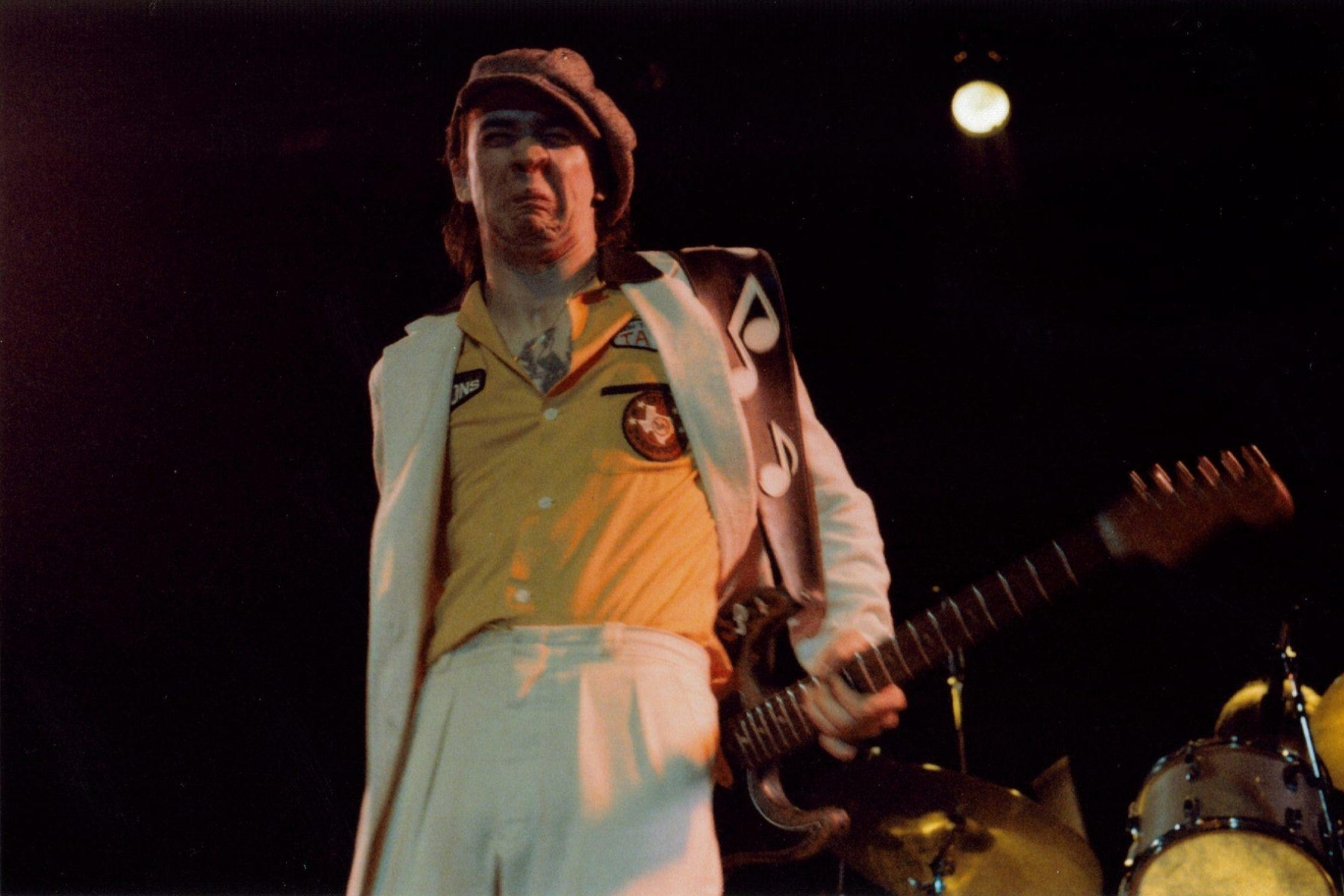

Maybe that’s where the money was, but it wasn’t what made the case important to me. Stevie Ray Vaughan was a rising Texas legend. He and his older brother Jimmie were guitar phenoms in the Dallas music scene when they were teenagers. They both later moved to Austin, where Jimmie’s career took off with his band, The Fabulous Thunderbirds. By any measure, Stevie was the better guitarist of the Vaughan brothers, but he insisted on playing the blues, a style that had limited appeal during the heavy metal ’70s and techno pop ’80s.

Stevie got his first big break at the Montreux Jazz festival in 1982, where his ferocious Jimi Hendrix style wrapped in Muddy Waters soul left some of the audience in rapturous tears and others booing in anger at the radical departure from the jazz they had come to hear.

A record deal followed that led to commercial success, lots of touring, and the nonstop partying that such a lifestyle seems to demand. Stevie Ray Vaughan was on his way, almost.

Drugs and alcohol brought the party to an end when Stevie suffered a physical and emotional breakdown while on tour in Europe in 1986. He was admitted to rehab and, against all odds, emerged sober and more focused on his music than ever. It was like a second career taking off, leading to the release of his most successful LP, In Step, in June of 1989. The album title pronounced his continued sobriety, having walked a 12-step recovery program. Two of the songs, “Tightrope” and “Wall of Denial,” were cautionary tales about addiction and substance abuse, a topic Stevie discussed openly during public appearances and in the middle of concert performances. He not only overcame his addiction, he repeatedly warned others about the destructiveness of a substance abuse lifestyle.

Stevie and his band toured through the rest of 1989 and into 1990, culminating with a two-night gig opening for Eric Clapton at the Alpine Valley Music Theatre in Wisconsin, a two- hour drive northeast of Chicago. Both nights sold out to crowds of 40,000 each. The last night was capped with an encore jam session featuring Stevie Ray Vaughan, Clapton, Robert Cray, Buddy Guy, and Jimmie Vaughan, arguably the most talented group of guitarists ever gathered on single stage in the history of rock and blues. Less than an hour later, Stevie Ray Vaughan, the youngest of those musical giants, was dead.

The details of the Vaughan case engrossed me for months. The helicopter involved was a Bell Jet Ranger, capable of carrying a pilot and four passengers. Lawsuits had been filed on behalf of all four passengers against the helicopter operating company (Omniflight Helicopters), the aircraft manufacturer (Bell Helicopter), and the manufacturer of the helicopter’s engine (Allison Gas Turbine). Our firm represented Allison, and we were soon allied with Bell, given that the plaintiffs’ liability theories against Allison and Bell were distinctly different than those against Omniflight.

The NTSB accident report concluded that the helicopter flew into a ski hill shortly after lifting off from a golf course near the concert venue. The NTSB investigator analyzed the wreckage and interviewed various witnesses. Based on this limited effort, he concluded that the accident was caused by “pilot error,” with no evidence of any pre-crash mechanical failure. That raised a question, though. Why would a pilot fly a perfectly good aircraft into the side of a hill? It made no sense. Most pundits, then and since, latched on to the presence of patchy ground fog at the scene that night as the culprit. But the pilot should have easily cleared the ground fog just feet after taking off.

I needed to figure out what exactly happened to discover the facts that would exonerate our client. To do that, I needed an expert. I needed Joe Kettles.

Joe was an affable helicopter pilot turned expert witness with great credentials. He’d been a pilot for over 30 years, accumulating 20,000 hours of flight time. He was sharp, carried the wisdom of a man nearing 60, and had an infectious grin that endeared him to everyone he met. Joe wanted to rent a helicopter identical to the one involved in the Vaughan crash and fly it under the same conditions from the same liftoff point. I set about to make that happen.

The Bell and Allison defense teams assembled during a crisp, off-season day at the ski/golf resort in Elkhorn, Wisconsin. I briefed the team on what we knew up to that point.

After the last concert finished, four Bell Jet Ranger helicopters from Omniflight were to take Clapton and some of his entourage to Chicago. Three seats were reserved for Stevie Ray Vaughan, his brother Jimmie Vaughan, and Jimmie’s wife, Connie. At the last minute, the Vaughan brothers were informed that there was only one seat available instead of three, so Jimmie stayed behind with his wife.

The four aircraft were lined up, nose to tail, on a flat area of the golf course near a parking lot. Their engines were running and rotor blades turning when Stevie Ray Vaughan boarded the third aircraft along with Clapton’s manager, Bobby Brooks, Clapton’s body guard, Nigel Browne, and the assistant tour manager, Colin Smythe. The Omniflight pilot at the controls was Jeff Brown. Interestingly, of the four Omniflight pilots flying that night, Brown was the only one not certified to fly a helicopter in instrument conditions, meaning that conditions had to be such that he could fly the aircraft using only what he could see out of its windows. In fact, not long before the flight, Brown had failed an instrument check ride.

The Elkhorn golf course sits in a little valley with a ridge of hills that the helicopters had to clear before turning toward their destination. The plan was for each aircraft to take off in turn, climb out of the valley, and head for Chicago. There was patchy ground fog in the area, but the night was considered in “VMC” or Visual Meteorological Conditions. VMC meant the pilots wouldn’t need to refer to their instruments to fly, and an instrument certification wasn’t required. Jeff Brown was legally qualified for the flight.

All the aircraft were seen departing the golf course as planned about 40 minutes after midnight, but the third never arrived in Chicago. A search was initiated, and at 7 a.m., the wreckage was discovered strewn along a ski hill .6 miles from the golf course. The impact point was only 100 feet higher than the takeoff elevation and 50 feet below the summit of the 300-foot hill. The wreckage spread uphill toward the summit, indicating a high-speed impact, probably around 100 mph. There were no witnesses to the impact. All five occupants died instantly.

Joe wanted to make a flight at night first, to see what Jeff Brown saw. I would accompany him as his co-pilot, an extra set of eyes Jeff Brown didn’t have.

That night, Joe positioned the aircraft where we knew the third aircraft had been when it picked up Stevie and the others. It was dark, but the golf course was well lit from the nearby parking lot lights positioned atop tall metal poles. We didn’t have patchy fog to contend with, but otherwise the conditions were the same as those faced by Jeff Brown.

Joe lifted the helicopter off the ground and started a climb over the parking lot. Everything looked great until we got above the light poles. Then, we were blind. Our eyes had become accustomed to the lights from the parking lot. Once we cleared them, the hills surrounding the golf course obscured lights from anywhere else. It was like being in a dark hole. We had no visual reference of the horizon to tell us where the ground stopped and the sky began.

Joe instantly transitioned to instrument flying, asking me to “call” the horizon when it came into view. Seconds later we topped the ridge of hills, revealing the city lights beyond, blinking brightly along the route to Chicago and giving us a clear sense of what was up and what was down. It all lasted just a few seconds, but the experience gave Joe an idea he wanted to test in the daylight.

The next morning we repeated the maneuver. We flew over the parking lot, climbed for a few seconds, and poked out above the valley, never coming anywhere near the ski hill Jeff Brown ran into. To hit it, Brown would have had to turn right about 40 degrees and stopped his climb for a few seconds.

“It doesn’t make sense, Joe. How did he hit that hill?” I asked over the intercom.

Joe flashed his signature smile. “Let’s do it again. I want you on the controls with me this time but close your eyes when we clear the parking lot. Don’t open them until I say so. I want you to focus on feeling what I’m doing to the controls and what your body is telling you the aircraft is doing.”

The Bell Jet Ranger is like a sports car, sensitive and maneuverable. Small, even imperceptible control movements can make the aircraft change what it’s doing at any given moment. Like all helicopters, it’s flown with three basic sets of controls. The “collective” is a control lever located on the pilot’s left, and, when all else is in balance, it makes the aircraft go up and down. The “cyclic,” a stick located between the pilot’s legs that works like a joystick, essentially makes the aircraft go forward, backward, left, and right, depending on which way you push it. The last set of controls is the pair of anti-torque pedals, one for each foot. Their job is to keep the nose pointed forward in flight and turn the nose when hovering. Flying a helicopter requires simultaneous, coordinated movement of all the above, and moving one set of controls requires moving the others to keep everything in balance and headed in the right direction.

I was on the controls with Joe for the second daytime demonstration. I felt Joe pull up on the collective to make the helicopter rise, followed by left pedal input to counter the increased torque, and tilting of the cyclic to move the aircraft forward. Once Joe got the aircraft moving up and forward at the climb angle and speed he wanted, there was nothing to do but keep the controls where they were until we got above the ridge.

“Close your eyes,” Joe barked as we cleared the parking lot light poles.

Joe was simulating for me what Jeff Brown felt as he looked outside the helicopter into the few seconds of darkness before he got above the ridge line. As I sat there with my eyes closed I felt no change on the controls, absolutely none. Everything told me we were still in a straight-ahead, steady climb safely out of the valley.

“Open your eyes!”

There it was, heading toward us at a frightening speed — the ski hill. Joe pulled back on the cyclic and started an emergency climb, clearing the ground by mere feet.

Of course, it all made sense now. Fog had nothing to do with this accident. It was the parking lot lights and a pilot incapable of dealing with the visual black hole that lurked above them.

This was the first time Jeff Brown had flown out of the Elkhorn Valley at night. When he got above the parking lot lights, he experienced temporary blindness to what was outside the cockpit, something he hadn’t anticipated. If Brown had been instrument rated, like the other three Omniflight pilots, he would have quickly transitioned to the instruments inside the cockpit and continued the climb by using the artificial horizon and other well-lit indicators on the panel in front of him. He knew he needed to hold his course for only a few seconds, though, and then the city lights would pop into view, showing him the way to Chicago. Without realizing it, while staring into the dark abyss above the parking lot lights, he applied a slight, imperceptible pressure on the cyclic, just enough to bank the aircraft to the right and stop his climb. A few quick seconds later, instead of clearing the hills, he hit one. He didn’t even know anything was wrong until the instant before impact.

When we shared what Joe had discovered with the other parties to the lawsuit, the plaintiffs focused their efforts against Omniflight, the company that made the decision to assign Jeff Brown to the mission. Eventually all the suits were settled, with Omniflight picking up the bill for undisclosed amounts.

Who killed Stevie Ray Vaughan? Some might still say the pilot. But I believe Jeff Brown did exactly what his skill level allowed him to do, given the circumstances. He should never have been put in that situation in the first place.

Who’s to say what would have become of Stevie Ray Vaughan if he hadn’t boarded Jeff Brown’s helicopter that night? I like to think he would have stayed sober and blown our minds year after year with his inspired playing, maybe also exhorting us to turn in times of isolation and challenge to music and other elevating pursuits instead of the alcohol and drugs that caused him such pain. All I know for sure is that heaven picked up a hell of a guitar player. Rest in peace, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Bobby Brooks, Nigel Browne, Colin Smythe, and, yes, Jeff Brown.

Colin P. Cahoon is the author of the mystery-thriller novels The Man with the Black Box and Charlie Calling.