In July, when former PGA of America head Pete Bevacqua sprang for NBC Sports, it was board member Seth Waugh that was pegged as the replacement. A former Deutsche Bank Americas CEO, Waugh brings finance chops. And right away, he faced a gargantuan task in bringing together the deal for the association’s next headquarters.

The pieces of that deal, as you’ve heard by now, fell into place in Frisco.

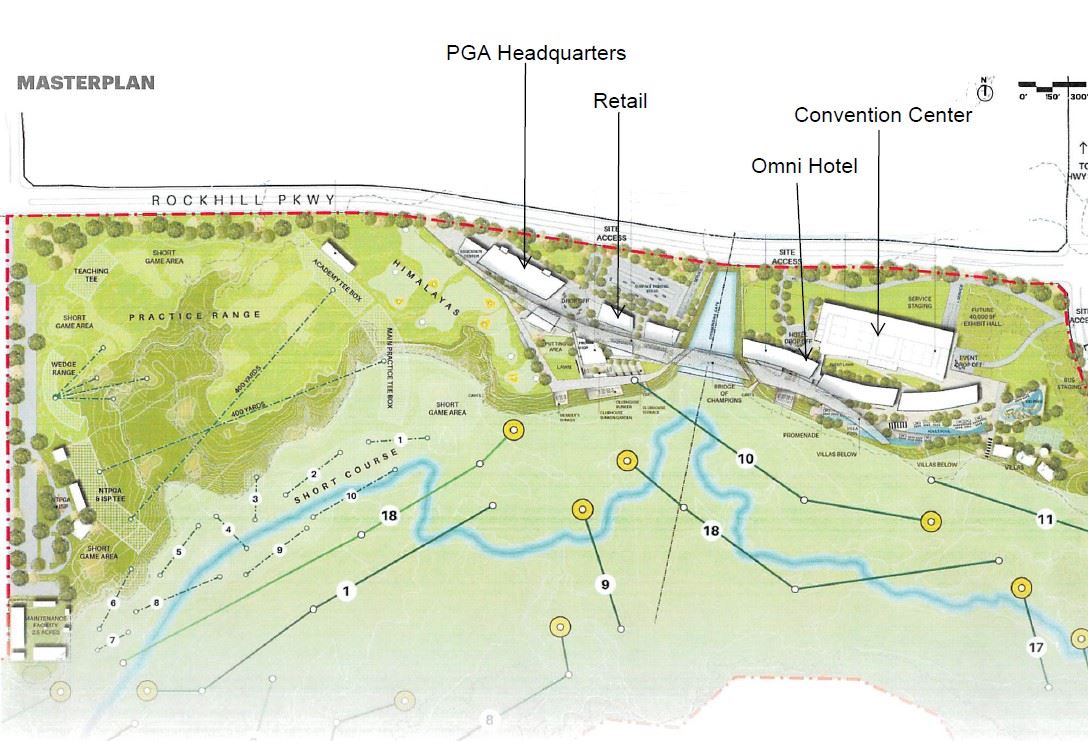

The specifics: it’s a 100,000-square-foot headquarters attached to a 500-guest room Omni resort, two 18-hole golf courses plus a 9-hole “short course,” 40,000 square feet of mostly golf-related retail, a 35,000-square-foot club house, and 127,000 square feet of meeting space. The resort will cost some $500 million to build, the headquarters some $30 million. It all sits on 600 acres, 540 of it for the golf courses.

And the thing that has golf fans most fired up: The site is guaranteed to host some majors. There will be at least two men’s PGA Championships and two women’s PGA Championships. There could also very well be a Ryder Cup.

It all comes at a steep price tag: while pledging just 100 jobs, the PGA of America could earn total incentives of over $160 million. The selling points undoubtedly revolved around much more than jobs, about it becoming a destination for golf fans and golf professionals alike. (An economic impact study estimated a $2.5 billion boost over the next 20 years.) Jonas Woods, an investor in the project, says the area could be akin to Scotland’s Old Course at St. Andrews, considered the oldest golf course in the world. “America’s version of the home of golf,” he says.

Woods took a leading role in the development of Dallas’ Trinity Forest Golf Club but has a smaller slice of this one. The major players were Dallas-based Stillwater Capital and Omni—the involvement of latter, as Waugh points out during our conversation, changed the way the PGA of America thought about the project.

During our chat, we walked through all that went into making the decision to move to Frisco, what it will take to land a Ryder Cup, Waugh’s vision that this will be more “Silicon Valley” than “home of golf,” and how his organization secured incentives that amount to $1.6 million per job.

Tell me about landing on Frisco, and about other places that you looked at and considered.

We did what everyone normally does which is to do a request for proposals. We got a bunch of responses. Our brand is pretty well-known and an attractive one in the sense of people wanting us to be around. We narrowed that down into another set of criteria, some of which was financial but a lot of which was kind of based on our mission and where we could accomplish it and what we could put in place. Some of the prominent names that showed up in the second round would be Charlotte, Phoenix, Atlanta, Palm Beach, Frisco.

When did you narrow it down?

I would say it was summer of ’17, roughly. Frisco really jumped out, immediately, for two reasons. One, the economics of it were really compelling. They checked all the boxes we were looking for in terms of a business-friendly place, golf DNA, weather—more or less 12 months of golf. And really what jumped out was what was available there, which was a raw piece of dirt. We’d been approached to consider having a championship course there previous to the RFP for the HQ.

The city of Frisco had previously approached you?

Right, exactly. They approached us on that. That might’ve been three years ago.

The same piece of land?

Yeah, more or less. The same part of town, for sure. That has been tweaked a little as we figured out flood plains and best grounds for golf. But it’s all roughly in the same area. It kind of bubbled up through the executive director of our North Texas section, who had a relationship with Frisco. We had heard of the town but nobody really knew it until we started going out there.

We started with economics but frankly, as we started to think about it, this was a generational kind of move here, once in a lifetime for us. What you could envision there became more important than whatever incentives you were getting. Incentives were important, and they were attractive. But there really wasn’t another site that could compete with the possible, if you will: two championship golf courses, hopefully the best training facility on the planet after we design it, another short course. We love the fact that it’s owned by the town and will have public access—speaks to a lot of what we stand for. The ability to not only build our headquarters but significant retail for us and for others. We think there could be an interesting hall of fame component to it.

Was it a deal breaker if it didn’t have the space for all those components? Was it always going to be two courses and a huge training facility? Or did it become what it became because Frisco enabled all those components?

The answer is no and yes. We always wanted it to have golf. We always wanted it to have one-stop shopping where we could have our headquarters but also have it be golf-related, if you will. 18 holes wasn’t a deal breaker, if that’s what it was.

It needed to have enough. It would’ve been really hard to have a totally urban location. Some of the RFPs, if I recall, you might’ve had a short drive to something that was golf-related as oppose to walking out your back door and it’s there. But there was no other proposal that had this raw piece of clay that we could mold into what we’re envisioning now.

So you narrow it down in summer 2017. Take me along that timeline a little further. It was March that the report hit saying this is more or less a done deal, you’re coming to Frisco. You deny the report. What was going on behind the scenes? Had you made a decision?

No, not at all. We had informed the board. It was very much in play. I would probably characterize it as our first choice, if everything aligned, at that point. But it was by no means a done deal. Palm Beach was still very much in play. Look, we’ve been very happy with Palm Beach. We’ve been there since the ’60s. It is, if not the, one of the golf capitals in the country because of the weather and DNA. There’s a lot of history there and a lot of lives.

Every deal has its ups and downs. The dream was always the same. The realities ebbed and flowed. Omni entering the picture changed everything dramatically, because they have enormous credibility in the marketplace and have real equity they can commit. They don’t have to go raise money to do something. That changed things, I think, for the city. It certainly changed it for us.

When did they enter the fray?

It was sort of right around in there, in the spring, I want to say. Whether it was before or after that article, I don’t quite know. [ed note: Omni’s Blake Rowling says Omni was already involved at the time the article was published.]

Pete Bevacqua was still in the CEO seat at that point. He certainly liked the deal, as we all did. The board began to get more comfortable with it. Any time you’re making a, call it, 50-year decision—a generational kind of decision—obviously you’re going to take your time doing them and make sure you really cross every T and dot every I. There was a lot of discussion at the board level for a long period of time about this, and an enormous amount of diligence.

When you have five parties—plus the town, plus the state—it was a complicated deal and took a lot of time and a lot of work.

You were able to snag a really healthy incentive deal, especially when you think of it on a per-head basis. How were you able to convince the powers that be that this was ultimately going to be worth it for them?

It was really important to them that it be the headquarters, and it is. Well, it will be when we get there in three or four years. That was a really big element of it. We did decide over the summer that the risk of closing Florida completely was too high in the sense of taking two or three years to move it across the country. The cost of that from a relocation perspective, relative to some of our operational jobs, didn’t make a lot of economic sense. The number of bodies changed a little bit in that we have and will continue to have a reasonably significant presence in Florida.

We’re going to build 100,000 square feet. We wouldn’t be building that if we didn’t think we were going to fill it. Our growth will be in Frisco, not anywhere else. Over time we think there will be significantly more bodies. We didn’t want to over-promise and under-deliver on the amount of bodies. We think it’ll be more than 100 but we were very comfortable saying that. Over time, if you do the math, 100,000 square feet is a lot more than 100 people. [ed. note: Based on 2017 averages, 100,000 square feet could hold about 650 workers]

Or giant offices.

Right. Well, I’m going to take 50,000 of it myself. (laughs) I’m going to have a bigger one than Jerry Jones.

I was the CEO of Deutsche Bank and we ran the Deutsche Bank Championship in Boston. Every year, the governor would come and thank me because they estimated we would bring somewhere between $75 million and $80 million in revenue to the area, for a normal PGA Tour event. The multiple around that for a major is significant, and Dallas as a market is significant. Look what the Cowboys do and look what the Mavs do when they’re playing well. There hasn’t been a major championship in decades. Those kind of events bring economic value to Frisco, branding to Frisco, tourism to Frisco. Without us, there isn’t a resort. There isn’t two golf courses for public use. There isn’t that retail. By the way, we’re developing a whole side of the town; the reason that land is there is because that side hasn’t been developed yet.

I think it’s a very fair deal for both sides in the sense that, yeah, we’re getting incentives to move across the country. We’re taking risk to do that. We’re bringing major championships, potentially a Ryder Cup, and our brand there. So, it’s kind of more than jobs.

What’s the Ryder Cup contingent upon?

It’s just making sure that the golf course and the venues work for that kind of a scaled thing. Coming back from Paris, the Ryder Cup is no longer a golf tournament, it’s a rock concert, a four-day rock concert. Making sure that the course is of the quality and the facility can handle it. It’s hard to commit to something before it’s built. But we have every expectation it will be everything we dream it to be.

The expectation is not that both courses would be major-worthy, correct?

Probably not. One would be more every day, not a resort course. It would be certainly long enough, but not designed with that in mind.

And then the short course, how short?

I don’t want to give you numbers that I don’t know. It’s nine holes. It’s not strictly a par 3; I think there will be some par 4s in there. But I would guess it’s somewhere in the 2,000-yard, 2,500-yard (arena). These things haven’t all been designed yet, either. But I think it’s meant to be a fun place to go play and play in an hour and a half instead of four.

What kind of public access are we talking about for these courses?

The town will own them. The Omni is going to have control, because of the resort, of a number of the tee times. Residents will have access—it’s not going to be specific windows, just an amount of tee times that the resort can reserve. And then, it won’t just be majors going on there. There will be more day-to-day events, member events, tournaments. Obviously, that will block out. But residents will have significant access to it. That’s one of the reasons the town is doing it, for sure.

What kind of jobs are going to be moving here in the short- and long-term?

Our membership will be there. Our education will be there. Most of our senior staff, including me, will be there. A lot of our championship staff will be there. We’ll have commercial interests there, as well.

I talked to Jonas Woods earlier, and one of the things he said was that this has the potential to be America’s version of the home of golf—

I think it could be golf’s Silicon Valley. The home of golf is St. Andrews, which is a destination where you go to play, you feel it, you buy old clubs and wear goofy hats. I think this will be a destination.

But I think we’re going to attract a lot of other golf interest. Imagine equipment companies, imagine physios that are trying to be around the game, entrepreneurs that are trying to figure out a new software or a new gadget that helps you play the game. I think we’re going to have a really vibrant place in the country.

It’s not going to be the day we open, but I would hope that we wake up 10, 15, 20 years later and we’ve had a huge impact on the game because Frisco has become a kind of think tank, slash laboratory, slash economic engine for golf.